We all know about milk fever (clinical hypocalcemia) right? And we all know that it can be stressful if we get many of these cases? But how much do we know about the not immediately visible form of this disease, called subclinical hypocalcemia?

Some farms encounter issues with wobbly and down cows due to milk fever more than others, but it’s hard to find a farm that does NOT have to treat a single case. World wide (including NZ) the incidence of clinical hypocalcemia over calving is on average in the range of 3-7%. The clinical cases are just the tip of the iceberg, for every one clinical case there will be 5-7 sub-clinical cases within the herd. Studies have shown that the average incidence of sub-clinical hypocalcemia post calving in NZ is 52% (half your herd), making this potentially an invisible problem on your farm.

Whoever has ever tracked their clinical milk fever cows during the milking season would have probably found that these cows also were more likely to have had mastitis, (endo)metritis, other diseases and a higher proportion of them ended up being late calvers or NOT in calf at all. Similar risk factors are linked to sub-clinical hypocalcemia. So how does this all work?

Lets recap the background of hypocalcemia:

At calving, a dairy cow must switch from being dry to lactating, rapidly adapting to the nutritional demands of milk production. A crucial mineral component of milk is calcium and at calving there is a sharp increased requirement for calcium. To get an idea of how much calcium is required to make colostrum for example you need to know that for every 10 kg of colostrum 23 grams of elemental calcium is required. So a cow producing 25 kg of colostrum will have to replace her total blood calcium level every hour!

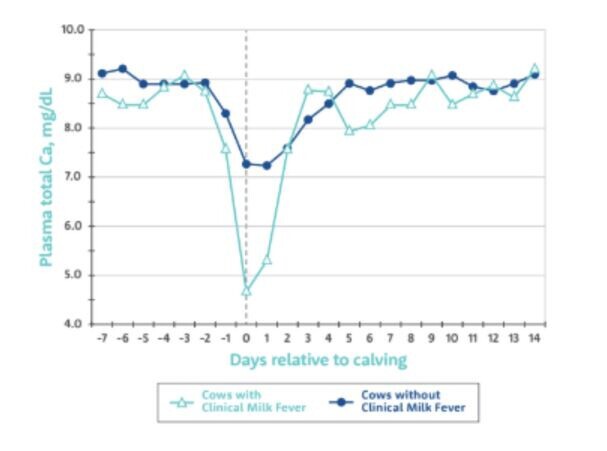

Calcium has several important roles inside the cow, including the mineralisation of bone and the correct functioning of muscles. The sudden increased requirement for calcium around calving will lead to a measurable fall in blood calcium, referred to as hypocalcemia. So to some extent there is a natural dip in calcium occuring around the time of calving no matter what. However it is the extend of the dip and the length of time of the dip that determines if a cow develops clinical hypocalcemia (milk fever), leading to increasing paralysis of muscles, or if she has a sub-clinical form of hypocalcemia where blood calcium levels only just drop below adequate levels without showing too many obvious signs in the cow’s appearance.

We all know about milk fever (clinical hypocalcemia) right? And we all know that it can be stressful if we get many of these cases? But how much do we know about the not immediately visible form of this disease, called subclinical hypocalcemia?

Some farms encounter issues with wobbly and down cows due to milk fever more than others, but it’s hard to find a farm that does NOT have to treat a single case. World wide (including NZ) the incidence of clinical hypocalcemia over calving is on average in the range of 3-7%. The clinical cases are just the tip of the iceberg, for every one clinical case there will be 5-7 sub-clinical cases within the herd. Studies have shown that the average incidence of sub-clinical hypocalcemia post calving in NZ is 52% (half your herd), making this potentially an invisible problem on your farm.

Whoever has ever tracked their clinical milk fever cows during the milking season would have probably found that these cows also were more likely to have had mastitis, (endo)metritis, other diseases and a higher proportion of them ended up being late calvers or NOT in calf at all. Similar risk factors are linked to sub-clinical hypocalcemia. So how does this all work?

Lets recap the background of hypocalcemia:

At calving, a dairy cow must switch from being dry to lactating, rapidly adapting to the nutritional demands of milk production. A crucial mineral component of milk is calcium and at calving there is a sharp increased requirement for calcium. To get an idea of how much calcium is required to make colostrum for example you need to know that for every 10 kg of colostrum 23 grams of elemental calcium is required. So a cow producing 25 kg of colostrum will have to replace her total blood calcium level every hour!

Calcium has several important roles inside the cow, including the mineralisation of bone and the correct functioning of muscles. The sudden increased requirement for calcium around calving will lead to a measurable fall in blood calcium, referred to as hypocalcemia. So to some extent there is a natural dip in calcium occuring around the time of calving no matter what. However it is the extend of the dip and the length of time of the dip that determines if a cow develops clinical hypocalcemia (milk fever), leading to increasing paralysis of muscles, or if she has a sub-clinical form of hypocalcemia where blood calcium levels only just drop below adequate levels without showing too many obvious signs in the cow’s appearance.

Hypocalcemia is often called a “gateway disease” as a drop in calcium will suppress immune function (resulting in metritis or mastitis); it will depress dry matter intake (leading to decreased energy intake and therefore ketosis) and it will decrease magnesium and phosphorus levels in the cow (complicating metabolic disease). Hypocalcemia is associated with poor fertility as trial work has shown that cows with hypocalcemia are 44% less likely to hold to 1st service and have 69% increased risk to get culled during or at the end of the milking season.

Having good transition management is crucial when it comes to the prevention of sub-clinical metabolic disease. Despite all good transition efforts, there will always be some at risk cows in each herd, these cows are at higher risk of subclinical hypocalcemia. Typical at risk cows for developing hypocalcemia are:

- cows with a history of metabolic disease

- older cows (over 3rd lactation)

- high yielding cows

- lame cows

- fatter cows

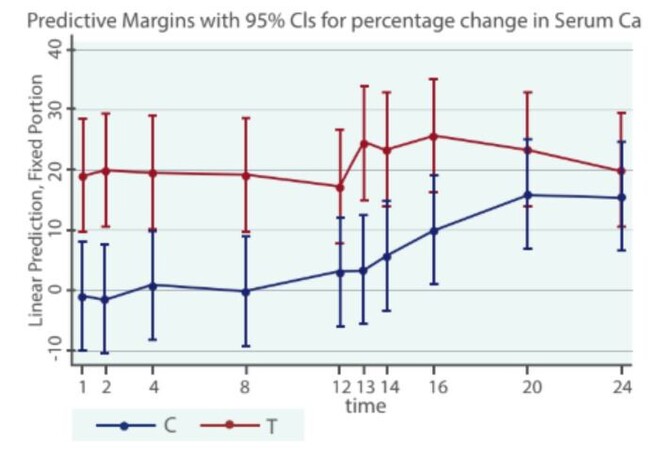

There is now an easier, well researched solution on the NZ market: Calpro Bolus is the only ACVM authorised, peer-reviewed intra-ruminal calcium transition bolus on the NZ market. TheCalpro Bolusdelivers 43 grams of elemental calcium in the form of two essential types of calcium: calcium chloride (rapidly absorbed) and calcium sulphate (slow release). Together these two types of calcium provide approx 12 hours of increased calcium coverage. Ideally two boluses need to be administered 12-15 hours apart to provide a sustained increase in serum calcium over 24 hours.

Table: Difference in serum calcium levels in Control (blue) vs Calpro bolus treated (red) groups

Our VetSouth clinics are stocking these Calpro Boluses now, so ring our lovely retail team to place your spring order today. If you are keen to find out more about these boluses and/or are keen to discuss your general transition cow management, get in touch with your KeyVet for a more in depth conversation.

- Georgette Wouda