You are heading out to check your horse in his paddock on a sunny Sunday afternoon. You notice that he is now severely lame on one limb and is standing with his toe pointed. You lift the leg to assess his foot and see a nail protruding from the sole of his hoof!

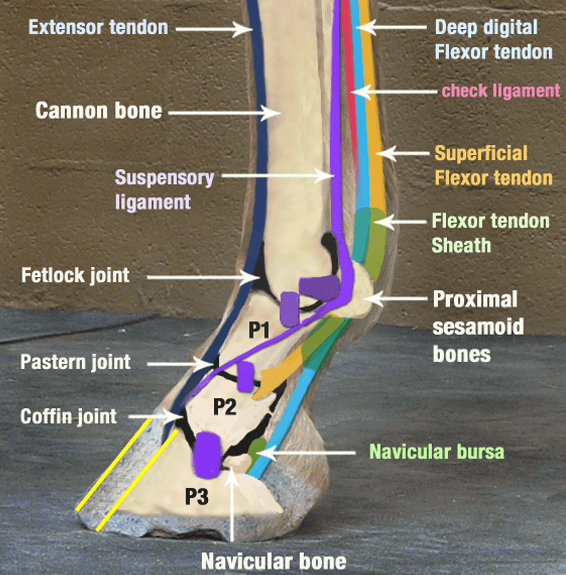

Solar punctures should always be treated as potential emergencies - we are particularly concerned about penetrating injuries to this area as the foot and lower limb contain many sensitive and vital structures. Damage or infection in these areas can cause career-ending lameness or can even be life threatening. Within the foot, we can appreciate (Figure 1):

- The coffin bone and the navicular bone

- The deep digital flexor tendon and impar ligament

- The coffin joint

- The navicular bursa and digital tendon sheath (sheaths encasing the tendons and allowing them to glide smoothly over bone and around corners)

- The digital cushion

These structures lie very close to the ground - there is only on average 3cm from the sole of the foot to the navicular bone in the average sized horse.

Why are we concerned about infection?

There are bony structures, tendons and ligaments, and synovial structures within the foot. A penetrating injury that contacts the bone can lead to an infection called osteomyelitis or septic pedal osteitis if the infection affects the coffin bone. Infections within the bone are tricky to treat once they become established and can cause permanent damage to the bone structure and integrity.

A penetrating wound that involves a synovial structure, such as those affecting the digital tendon sheath, navicular bursa or the coffin joint, can be equally or more devastating than a wound that contacts bone. When an infection develops within a synovial structure, the body’s response to fight the infection causes a large inflammatory response. Unfortunately, this inflammatory response also causes damage to the cartilage, tendon and lining of these structures, which can be permanent. It can take only a matter of hours to days for irreversible damage to be done that can cause chronic lameness.

We can also assume that if the wound has contacted the navicular bone, or involves the navicular bursa or the tendon sheath, that it has likely passed through the deep digital flexor tendon on it’s path. This can set up a septic tendonitis and cause local destruction of the tendon or adhesions again leading to chronic lameness.

How do we approach these cases?

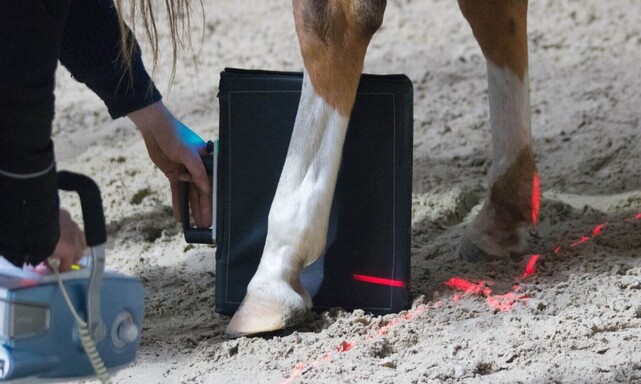

The initial reaction to seeing a nail or other object in the foot is most likely to want to pull it out. This is not always the most helpful approach however in terms of figuring out which structures have been compromised. It can be useful to x-ray the foot and the limb with the object still in place. This enables us to see exactly where the object has been and which structures we need to evaluate further. This is particularly useful if the object has penetrated through the frog, as the elastic tissue in this area can often make it difficult to find the tract again once the object is removed.

The most important part of the initial approach is to ensure that the object does not move any further into the foot. The horse should not be moved until the object has been stabilised. We can do this by placing a block of wood or similar material on the foot around the nail or object, preventing the horse from weight bearing on this region of the foot and driving the object further.

After the initial assessment with the vet, further investigation and treatment will be recommended. The location of the injury will determine the requirement for further diagnostics. Referring back to the diagram of the anatomy of this area, we can see that the most concerning injuries are those in the middle to the back of the foot, including through the frog. Penetrating injuries around the edge of the foot have a higher chance of missing the vital structures contained in this region.

Further diagnostics might include x-rays - with or without contrast material, ultrasound, joint tap or tendon sheath taps and fluid pressure tests of these areas. The latter allows direct sampling of potentially affected joint or tendon sheath to assess the fluid within these structures - analysing the types of cells present can indicate if the structure is infected. A fluid pressure test involves injecting sterile saline into the joint or tendon sheath. If fluid begins to run from the site of the puncture, we can confirm communication between the puncture wound and the joint or tendon sheath.

Immediate, aggressive treatment is essential to ensure a good amount for infected joints or tendon sheaths. Both systemic and concentrated local antibiotics are required, along with anti-inflammatories for pain relief. Flushing of the infected structures may also be necessary. Depending on the severity of the infection, this can either be performed with a through and through lavage in a standing patient or it may require a general anaesthetic to allow a camera to be passed into the joint or tendon sheath to assess the damage and allow full decontamination of the area.

The most important part of the initial approach is to ensure that the object does not move any further into the foot. The horse should not be moved until the object has been stabilised. We can do this by placing a block of wood or similar material on the foot around the nail or object, preventing the horse from weight bearing on this region of the foot and driving the object further.

After the initial assessment with the vet, further investigation and treatment will be recommended. The location of the injury will determine the requirement for further diagnostics. Referring back to the diagram of the anatomy of this area, we can see that the most concerning injuries are those in the middle to the back of the foot, including through the frog. Penetrating injuries around the edge of the foot have a higher chance of missing the vital structures contained in this region.

Further diagnostics might include x-rays - with or without contrast material, ultrasound, joint tap or tendon sheath taps and fluid pressure tests of these areas. The latter allows direct sampling of potentially affected joint or tendon sheath to assess the fluid within these structures - analysing the types of cells present can indicate if the structure is infected. A fluid pressure test involves injecting sterile saline into the joint or tendon sheath. If fluid begins to run from the site of the puncture, we can confirm communication between the puncture wound and the joint or tendon sheath.

Immediate, aggressive treatment is essential to ensure a good amount for infected joints or tendon sheaths. Both systemic and concentrated local antibiotics are required, along with anti-inflammatories for pain relief. Flushing of the infected structures may also be necessary. Depending on the severity of the infection, this can either be performed with a through and through lavage in a standing patient or it may require a general anaesthetic to allow a camera to be passed into the joint or tendon sheath to assess the damage and allow full decontamination of the area.

- Grace Reed