Vet Zoe was called out to a Southland farm last winter after several pregnant ewes were found dead on crop.

Last winter, we were called out to a farm in Southland after a farmer found several dead sheep and others staggering around, as if drunk, on a kale crop.

Suspecting nitrate toxicity, the farmer moved the rest of the mob off the kale and onto grass. Unfortunately, as they were being shifted, the ataxic (uncoordinated) ewes all proceeded to pass away within minutes.

The 700-strong mob was made up of two tooths scanned with triplets and twins and they had been transitioned onto the crop a week before without any issues.

When I arrived on-farm and checked the break, I found that the mob had grazed it down hard (to stubble). The crop had been sown in January and no additional fertiliser had been applied to the paddock since February, when minerals and DAP were put on.

A quick clinical exam of one of the down ewes showed the following symptoms:

High heart rate

High respiratory rate

Depressed mentation (unable to hold their head up)

Mucous membranes, especially conjunctiva, were muddy brown in colour instead of the normal pink shade

Oral mucous membranes were pale

Temperature was normal.

In combination with clinical history, nitrate poisoning was deemed the most likely cause.

The effects of nitrate

In ruminants, excess levels of nitrate are converted into nitrite in the rumen. This is then absorbed into the bloodstream and binds with haemoglobin on red blood cells, preventing oxygen carrying capacity and creating methaemoglobin.

This lack of circulating oxygen, or methaemoglobin, results in the brown discolouration of mucous membranes and death can occur rapidly due to lack of oxygen.

Treatment options

There is treatment for nitrate toxicity with methylene blue (dissolved in sterile saline), which converts methaemoglobin back to haemoglobin and restores blood oxygen levels. This treatment must be given into the vein (IV) and, if given in time, can prevent further deaths.

However, it can take only an hour for an animal to ingest enough toxic feed to have clinical signs, which can progress rapidly from staggering, rapid breathing and salivating to death (which is often the first sign of the issue).

The ewe examined was given methylene blue (it was noted that her blood was also brown in colour whilst giving the IV injection). Then came the conundrum of what to do with the rest of the mob!

For ewes with borderline methaemoglobin, any stress (including moving the animals) may tip them over the edge of hypoxia (low levels of oxygen in body tissues) and result in death. We decided that moving them to yards a few paddocks away may result in more problems, so instead did a ‘slow’ look through the mob to treat any obviously sick ewes. We identified a further two.

Some kale plant samples were then collected from different areas of the break for testing back at the clinic.

The plan with the rest of the mob was to keep them on grass and feed supplementary baleage to try and dilute the effect of the nitrate. We advised the farmer that they may see some abortions in the mob and further deaths overnight.

Testing

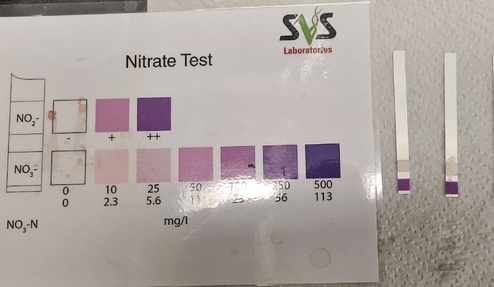

On testing, the plants were split into sections of leaf, stem and bulb. The results, shown below, confirmed nitrate toxicity as the cause and we advised the farmer to keep the rest of the mob on grass for at least a week to allow red blood cells to recover and regenerate.

With high nitrate levels (500-600mg/l), it can take many weeks for levels to drop in the plant. Brassicas, ryegrass and cereal crops are particularly susceptible to high nitrate and any new pastures sown in autumn.

Possible causes?

The farm’s agronomist suggested possible risk factors in this case were the drought in spring followed by heavy rainfall, the fact the kale was a secondary crop to grass rather than having an intermediate crop, cloudy weather, and rapid growth of the plant.

DairyNZ outlines some other potential risk factors for toxic levels of nitrate:

Plants under stress, including loss of leaf area or damage due to pests/frost

Wilting due to low moisture conditions

Young, immature plants

Using high levels of nitrogen fertiliser late in the season

Animals under stress e.g. pregnancy, lactation, immunosuppression

Low temperatures - nitrates can be absorbed by plants at low temperatures, but are not converted quickly into protein during cold spells thus levels build up

High acidity soil, sulphur and phosphorus deficiencies, and low molybdenum increase nitrate uptake by plants.

In this particular case, the gathering of animals at one area of the paddock also contributed to excess nitrate levels due to pugging.

We re-tested the paddock after one week to assess levels, which had reduced to 100mg/l at the top part of the paddock and 10mg/l at the bottom. It was, therefore, decided to feed only from the bottom part of the paddock, if necessary, for the sheep, and to place non-pregnant beef animals on the top section.

Ways to minimise risks

Test any feed - this is the only way to quantify levels if you think feed is at risk;

Feed silage/hay before moving animals to a new break to ensure they are not hungry when shifted;

Move breaks in the afternoon to allow for maximum time for photosynthesis in plants (converts nitrate to protein). Take care on overcast/cold days;

Ensure grazing is not down to the stem, or ‘hard’ grazing, as nitrate levels are often higher in the stem/bulb. This may require larger breaks or more supplementary feed first;

Check animals one hour after moving the break. This should be done after each new break as nitrate levels can vary across paddocks.